Fidaq Zaatar, Contributing Author

Al-Khansa Primary School

State of Palestine

The students I teach are first grade students, all 7 years of age and all female. They come to school despite the level of poverty they experience, the family and social problems they face, and/or the psychological pressures they suffer because of the political situation we live in. Despite all this, I consistently employ various methods that promote joy and hope and a more meaningful life. These methods include structured play, music, drama, active learning, storytelling, games, and dissemination of health and cultural awareness.

Our learning space is home to the common collection of subject area learning that students in Palestine experience. This includes Arabic, mathematics, science, national and civic education, religion, and sports education. Most of all, I teach them how to love life. Students learn how to achieve their hopes and are determined to challenge these dreams as active members of society.

I have implemented an initiative called “children of the day – future leaders” based on planting seeds essential to the students of the first grade who will grow to become global citizens.The flexibility of the learning space supports the teaching methods and learning strategies I teach. This supports cooperative learning, is encouraging critical thinking, and creative thinking. Tables with wheels, a large carpeted space, and natural light all contribute to the students affect toward the learning. This design element is critical to supporting resilient, independent learners.

I have implemented an initiative called “children of the day – future leaders” based on planting seeds essential to the students of the first grade who will grow to become global citizens.The flexibility of the learning space supports the teaching methods and learning strategies I teach. This supports cooperative learning, is encouraging critical thinking, and creative thinking. Tables with wheels, a large carpeted space, and natural light all contribute to the students affect toward the learning. This design element is critical to supporting resilient, independent learners.

This is a learning space that produces global citizens. These are students who are cultured and creative, responsible, collaborative, respectful of diversity, champions of justice and peace, are true to their values, and focused on knowledge and skills to make a better life. The design of our space includes opportunities for students to cultivate leadership, something they will someday use to contribute to society.

This is a learning space that produces global citizens. These are students who are cultured and creative, responsible, collaborative, respectful of diversity, champions of justice and peace, are true to their values, and focused on knowledge and skills to make a better life. The design of our space includes opportunities for students to cultivate leadership, something they will someday use to contribute to society.

Fidaq Zaatar believes in the sanctity of education and the role of the teacher in building and developing the community, which drew her to work in the education profession. She started teaching in 2000, in a village in the eastern city of Nablus, working as a teacher for the second grade for five years. After that, she was transferred to Al-Khansa Elementary School for Girls. She has garnered many important achievements and recognitions during her career, including being named a Global Teacher Prize Finalist and a Qudwa Fellow.

I’m a natural science teacher. The concept of Space2Learn really resonates for me as I wanted to go to space – as in outer space – to explore and learn. I applied to NASA’s Educator Astronaut Corps and was in the top 10% of finalists. While I didn’t get to go to space, I have made sure that students get outside of indoor classroom spaces into the local environment.

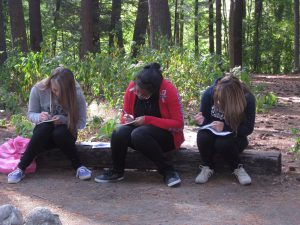

I’m a natural science teacher. The concept of Space2Learn really resonates for me as I wanted to go to space – as in outer space – to explore and learn. I applied to NASA’s Educator Astronaut Corps and was in the top 10% of finalists. While I didn’t get to go to space, I have made sure that students get outside of indoor classroom spaces into the local environment. Placing their feet directly on the Earth makes them global students. The student’s learning space is the surrounding air conditions, what’s in the distance and close up, and in the space between students, as they observe and ask questions. All of this, however, has to be grounded with strong content, competency development, and rigorous expectations. Getting your students outside is fantastic, but you have to be highly organized to make it more than a walk in the park. Here’s a strategy to communicate to students and guide your outdoor education work…

Placing their feet directly on the Earth makes them global students. The student’s learning space is the surrounding air conditions, what’s in the distance and close up, and in the space between students, as they observe and ask questions. All of this, however, has to be grounded with strong content, competency development, and rigorous expectations. Getting your students outside is fantastic, but you have to be highly organized to make it more than a walk in the park. Here’s a strategy to communicate to students and guide your outdoor education work… High school science students learn outside. Why not learn science where the science naturally exists? Biology, botany, ecology, environmental science are just some of the topics to explore. I’m inspired to see students engaged in outdoor activities using the strategy above as the conduct cloud observations, tree measurements, biodiversity mapping, soil sampling, specimen collection and more.

High school science students learn outside. Why not learn science where the science naturally exists? Biology, botany, ecology, environmental science are just some of the topics to explore. I’m inspired to see students engaged in outdoor activities using the strategy above as the conduct cloud observations, tree measurements, biodiversity mapping, soil sampling, specimen collection and more.